Archaeologists have discovered ancient and rare carvings of Assyrian gods in an underground complex in southeast Turkey. This unprecedented discovery could indicate that the most powerful empire in the world almost 3,000 years ago used a form of “soft politics” in one of its border regions.

The engraved scene depicts at least six gods, including Adad, the Mesopotamian storm god, the moon god Sîn, the sun god Shamash, and Atargatis, the region’s fertility goddess. It is described in an article published in the journal Antiquity.

The nature of the find is also unusual, as police found the underground complex in 2017 after tracking a secret passage from a modern house in the village of Başbük, about 50 kilometers from the town of Şanlıurfa.

The article’s co-author and philologist Selim Ferruh Adalı, from Ankara University of Social Sciences, says it seems the complex was first discovered many years ago, when the house was still under construction. construction. But this find was not reported to the authorities, as required by Turkish law; instead, the looters dug a tunnel between the house and the underground passageways. They ended up being arrested, and it seems that they did not damage this ancient work.

Mehmet Önal, lead author of the paper and head of the archeology department at Harran University in Şanlıurfa, first saw these underground carvings under the flickering light of a lamp.

“I felt like I was watching a ritual,” he recalls. “When I was confronted by the very expressive eyes and the majestic, serious face of the storm god Adad, I felt a slight tremor throughout my body. »

THE STYLE OF THE EMPIRE BLENDED WITH LOCAL SYMBOLISM

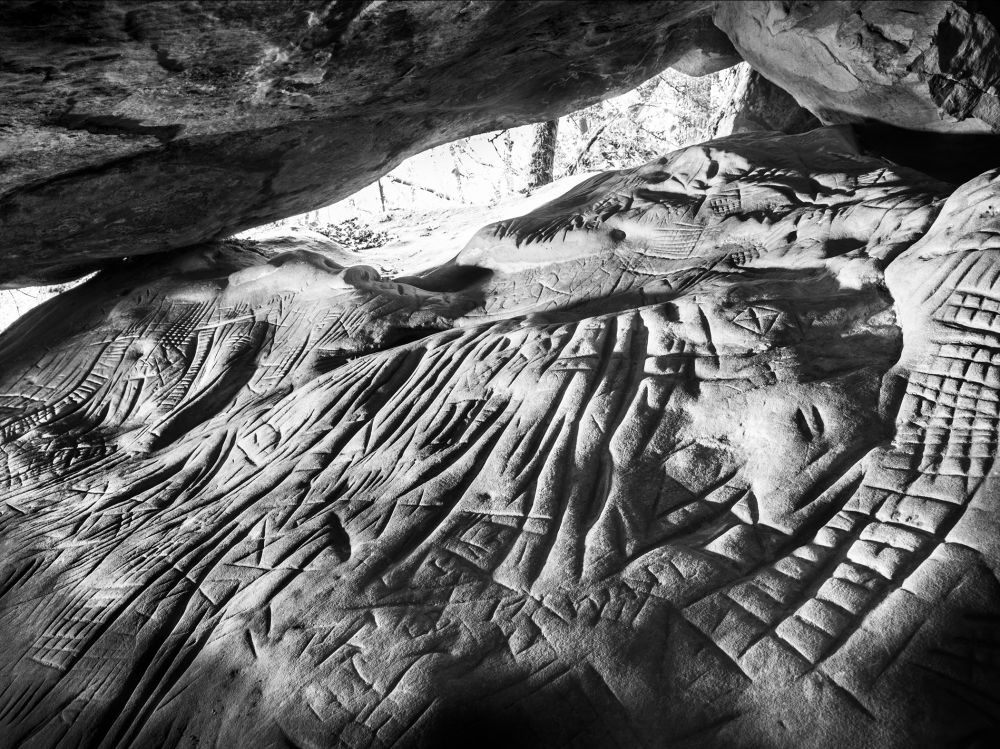

The underground complex is made up of hundreds of meters of passages, stairs and galleries carved into the rock. The complex and the carvings appear unfinished: scholars speculate that construction stopped unexpectedly, probably in the early 8th century BCE.

An inscription next to the carvings in Turkey seems to point to part of a name that researchers say reads “Mukīn-abūa.” It could be the Mukīn-abūa listed around 2,700 years ago in Assyrian records as being the governor of the provincial capital of Tušhan, about 145 kilometers east of present-day Başbük.

For Adalı, if this reading is correct, it could be that Mukīn-abūa ordered the construction of the underground complex and the making of the engravings, and that the work ceased when his role as governor ended.

Ancient deities are depicted in procession on a 3.5 meter wide rock panel. Six faces can be seen, and four of the gods are identifiable: the storm god Adad, for example, bears a trio of lightning bolts. Each of these delicately carved portraits, the largest of which is about 1 meter high, shows the head and upper body of a god. Lines of the illustration are highlighted in black paint, perhaps to serve as a guide to help the artists when cutting more stone to give relief to the figures.

Adalı notes that while some characteristics of the gods are typically Assyrian, such as their rigid stances and the particular style of their hair and beards, many of the details of the carvings in Turkey indicate strong influences from local Aramaic culture. The Aramaeans had lived in the region for centuries before falling under the rule of the Assyrian Empire which was expanding in the 9th century BCE, thus coming under the control of kings who lived far to the east, in the northern Mesopotamia.

The expert also observes that the inscriptions next to the carvings are written in Aramaic and give the Aramaic names of the gods, rather than their Assyrian names. “We mainly find Aramaic symbolism, mixed with Assyrian style,” he says, adding that this deliberate mixing could be an attempt by Assyrian rulers who were not there to fit in with local chiefs, rather than rule. by force.

Archaeologist Davide Nadali, from the University of Rome “La Sapienza”, agrees that this unique artistic blend of Assyrian and Aramaic characteristics sheds interesting political light on the relationship between the mighty empire and one of its main territories.

“The Aramaic inscriptions emphasize the intention to engage with local communities, [while] the use of Assyrian figurative style shows the need to interact with Assyrian political power,” he explains in an email. .

Comments are closed